July 31, 2013

My initial plan was to

return to Bishkek on Saturday, July 27th. I’d reserved a bed in the

Sakura hostel for the 27th-30th way back in June… but,

this being Kyrgyzstan, a wrench was (of course) thrown into my carefully laid

plans. This particular wrench came in the form of M., an American undergrad

student who, fresh off a year in Russia and a month in Tajikistan, was spending

a week or so in Kyrgyzstan before returning to the US. His local Kyrgyzstan

travel arrangements had been made through The London School. His plans were to

spend Thursday night at the Beach Camp and then return to Bishkek on Friday

night. Logically and logistically, it made far more sense for me to return to

Bishkek with him on Friday night than to have The London School arrange

separate travel for the both of us. Of course, the problem was that Sakura was

packed. I had a bed reserved for Saturday, but there wasn’t space for me for

Friday. We were too late in the planning stages to arrange a homestay through

The London School (such as the one where M. was staying), so I ended up

spending the night at the home of the director of The London School… where Aliman

and Murat from Toguz Bulak happened to be staying as well. (The director is, I

believe, the aunt of their mother.)

In the morning, after

a nice, late breakfast, I made my way to Sakura. When they’d said the place was

packed, I’d had no idea just how packed. There were only two dormitories when I

first stayed there back in May. In June, they opened a third dorm. All of the

beds in all three dorms were full, as were all of the private rooms. And the

floor on the third floor. And the rooftop patio. Considering the solitude in

which I’d spent the previous two months, it was all a bit much.

I had four full days

to spend in Bishkek, although I admit that I did very little. Most of the

Bishkek folks whom I know had left the sweltering heat of the city (and it was

boiling – in the upper 90s, sometimes topping 100F – every day I was there) for

the cool air and waters of Issyk Kul, and the temperatures made wandering about

the city a challenge. On the one hand, after having spent the entire summer being cold, this was quite a welcome change in temperatures. On the other hand... it was bloody hot. I didn’t even carry my DSLR with me most of the time, as

it was simply too hot to lug around something of that size. Yeah. Of course, as

the hostel was not air conditioned, I spent a good amount of time in

“expensive” (by Bishkek standards) restaurants with air conditioning: curry at

The Host, rabbit at У Мазая, Khachapuri at Mimino, pizza at VEFA, and a

calzone at Cyclone. (Cyclone has the best hot chocolate in the world, but as I

was so hot by the time I got there, I couldn’t bring myself to order it; I had

one of their milkshakes instead.)

Curry at The Host

Khachapuri Adjaruli at Mimino

'Hunted Rabbit' at У Мазая

The remains of my calzone at Cyclone

I didn’t just eat my

way through four days in Bishkek; I had errands to run, too. I had to return my

borrowed laptop to The London School, complete with the audio recordings of

myself which I had made for them, tape-scripts, edited texts, and photos of my

volunteering experiences. In turn, I finally received my stipend (haha). I then

spent most of said stipend mailing home the large box of gifts from host

families and students. I also finalized my souvenir/gift buying, and even

braved the heat to wander around the city (albeit with my point-n-shoot). I also managed to get a really great haircut at a place not too far from the hostel. And

that was it, really.

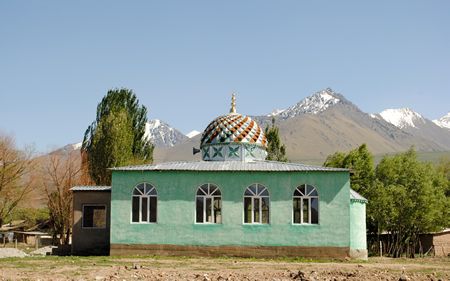

As you can see, the weather was gorgeous. But sweltering, absolutely sweltering.

A really lovely haircut, by a very nice woman... who I must admit was horrified by how long I'd gone since last dyeing my hair. Bishkek and the villages are really different worlds.

At 1:30am on July 31st,

three French tourists (who had been among the masses at Sakura) and I left the

hostel and headed for the airport. Checking in at Manas is definitely a lot

easier without four cats! I did, however, see an elderly gent traveling with

two small dogs – good times. I arrived in Istanbul at 7am local time, and got

to sit through a six hour layover. There was actually a later flight out of

Bishkek, but I would have had less than an hour to catch my flight to the

States. I hadn’t wanted to miss my connection, so I settled for six hours of

mind-numbing boredom. M, on the other hand, chose the latter flight. He and I

were supposed to be on the same flight from Istanbul to New York, but he didn’t

make it in time.

And that’s it, the end

of my summer in Kyrgyzstan. I leave you to contemplate a video I made showcasing how - despite New Zealand's attempts to convince us otherwise - Kyrgyzstan is indeed Middle Earth. You have to click here to download it; YouTube won't let me post it as they say it's a copyright infringement.