July 23, 2013

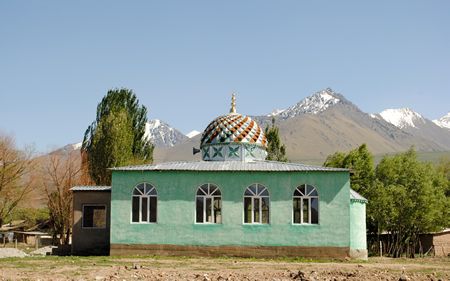

Kyrgyzstan is a

predominantly Muslim country. As a result, one of the first things that people

in the US typically ask me about my life in Kyrgyzstan is, “Do you have to wear

a headscarf when you’re there?” Um, no. However, after more than a week without

washing my hair, I generally do wear

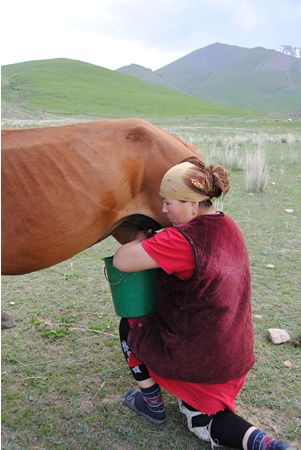

a headscarf; no one wants to see my greasy, unwashed head. Traditionally in

Kyrgyz villages, a headscarf is indeed worn by the women. However, the Kyrgyz headscarf is not a hijab. It’s more of a bandanna than

anything else. As the more conservative Saudi strain of Islam gains more of a

foothold in Kyrgyzstan, hijabs have

started to crop up here and there – but for the most part, it’s the Kyrgyz

bandanna-scarf or nothing. Foreign women are not at all expected to wear a

headscarf – unless, of course, they want to.

OK. Now that we’ve gotten

the scarf issue out of the way, let’s look at the other ways in which religion

affects the people of Kyrgyzstan. As I said before, Kyrgyzstan is a

majority-Muslim country. Similarly, the US can be considered a

majority-Christian country. Now, I’m sure that if you’re an American, you know

quite a few folks who self-identify as Christians – and who may even go to

Church regularly – but for whom religion has little effect on their lives.

Meanwhile, if you’re from (or have spent time in) the American Bible-belt,

you’ve probably met the sort of Christian for whom every facet of his/her life

revolves around the church, and who will want to talk religion – and

conversion, if you’re a non-believer – with you at any possible moment. Like

Christianity in the US, Islam in Kyrgyzstan runs the gamut, although in my

experience there seem to be far more folks who identify themselves as Muslims,

but who don’t think about religion all that much in general, whereas there seem

to be only a few on the ultra-serious end of the religion spectrum.

Bishkek, the capital, tends

to be filled with self-identified Muslims who believe in Allah and Muhammad and

the Koran, and who celebrate the major Islamic holidays, but who don’t really

think about religion all that much. I’ve met many Bishkekers who self-identify

as Muslims, but who smoke, drink alcohol, have pre-marital sex, don’t keep halal, wear short skirts, and don’t

cover their hair (the last two applying to women, obviously). Outside of

Bishkek (especially the more rural the area), women typically don’t smoke, have

pre-marital sex, or wear short skirts, although all but the most strict Muslim

women don’t drink alcohol. Most rural women do, however, cover their hair with

the Kyrgyz-style headscarf. Some rural Kyrgyz men do abstain from vices on

religious grounds, but smoking and drinking in particular are very common.

My host family in Toguz

Bulak self-identified as Muslim, but they were not an overly religious bunch.

Other than at the forty-days memorial service for Rakhat’s father, I never

heard them pray other than a quick ‘omin’ at the end of a meal or before a

sheep was slaughtered. They never spoke of religion. The call to prayer would

come and go and neither they (nor anyone else I witnessed in Toguz Bulak)

responded in any way. My host ‘parents’ did not drink alcohol themselves,

although many of their relatives did. Additionally, they operated a private

store from which they sold vodka to the locals. And you might remember the

great pleasure they seemed to derive from getting me plastered. So, religious,

but not overly so.

In contrast, my host

‘father’ in Bar Bulak was the local imam. On our drive from Toguz Bulak to Bar

Bulak, he brought up religion, assuming that I was a Christian: “So, what are

you – Orthodox, Catholic, or Protestant?” Me: “Um… I’m not anything.” Him: “Oh.

I guess you just haven’t thought about it yet. You’re young and probably very

busy. You’ll think about it more when you’re older.” I thought that was kind of

an odd thing for him to say to me, considering that he and I are the same age,

but that was it. That was the extent to which the local village imam and I

discussed religion.

Now, there were definitely

signs that my host family in Bar Bulak were religious (other than Kuban being

the local imam): they sent their eight year old son to a month-long Muslim

summer camp, Rita and Aidai would don

hijabs to pray – not necessarily five times a day, but roughly – although

they only wore them for prayer (the rest of the time they wore Kyrgyz

headscarves), Kuban and his son wore Islamic skullcaps, they kept halal, they didn’t smoke or drink

alcohol, and fasting during Ramadan was very important to them. And… that’s

really the extent to which I witnessed the practical effects of Islam on their

lives.

(As a side note, Kuban’s

call to prayer was always very beautiful and moving. He usually did it through

the loudspeaker at the village mosque, although he didn’t always make it there.

Sometimes the call to prayer went out from our backyard or from the yurt camp

by the lake. I really wanted to record him, but somehow that just seemed too

intrusive.)

Interestingly, Kuban’s

family is not overly religious. Most of his relatives live in the city of

Balykchy, which is half an hour or so away from Bar Bulak. As such, I saw many

of his relatives quite a few times during my stay. One of his sisters told me,

“You know, Kyrgyzstan isn’t that strongly a Muslim country. It’s funny that you

came here and got stuck with a fanatic like Kuban.” She said this quite

jovially. And it was funny, because he’s a far cry from what I would consider a

religious fanatic. I mean, once during dinner we watched an Islamic sermon on

TV. When it was over, we watched the last hour of Miss Congeniality. Anyway,

when I lost my voice, another one of Kuban’s sisters told me that I should come

and stay with her, as what I needed to cure my sore throat was a shot or two of

vodka, and I wasn’t going to get that from her brother.

Meanwhile, while Kyrgyzstan

is predominantly Muslim, there are a large number of Christians who live here

as well. Despite the dwindling population of ethnic Russians in Kyrgyzstan,

there are still quite a few Russian Orthodox believers in the country,

especially in Bishkek and Karakol. There are quite a few Christians of other

denominations in Bishkek, although few are ethnic Kyrgyz. Ethnic Russians,

ethnic Koreans, and ex-pats make up the bulk of the Christian community

throughout the country. Additionally, I have met quite a few local people who,

like me, are simply non-religious. I’ve even met a small handful of Kyrgyz

folks who are anti-religion in general. As far as I am aware, while there have

been inter-ethnic tensions and

violence within Kyrgyzstan, there has been little to no inter-religious tension or violence. I believe

that it is illegal to come to Kyrgyzstan for the purpose of proselytizing, but

if you simply come as a member of any faith – or of no faith – you should not

expect this to cause you any problems whatsoever.